Wynd Cottage, Whitby - Archaeological Description

This is the report of Historical Building Assesment we had carried out in 2023. The Assement was carried out by Dr James Wright FSA of Triskele Heritage. We can highly recomend the services he offers.

The full PDF of the Report is available to download here

For ease of navigation I've split the report over three web pages and put the photos, illustrations and maps etc in with the text.

2. Archaeological Description (this page)

Archaeological Description

Exterior Elevations of the Property

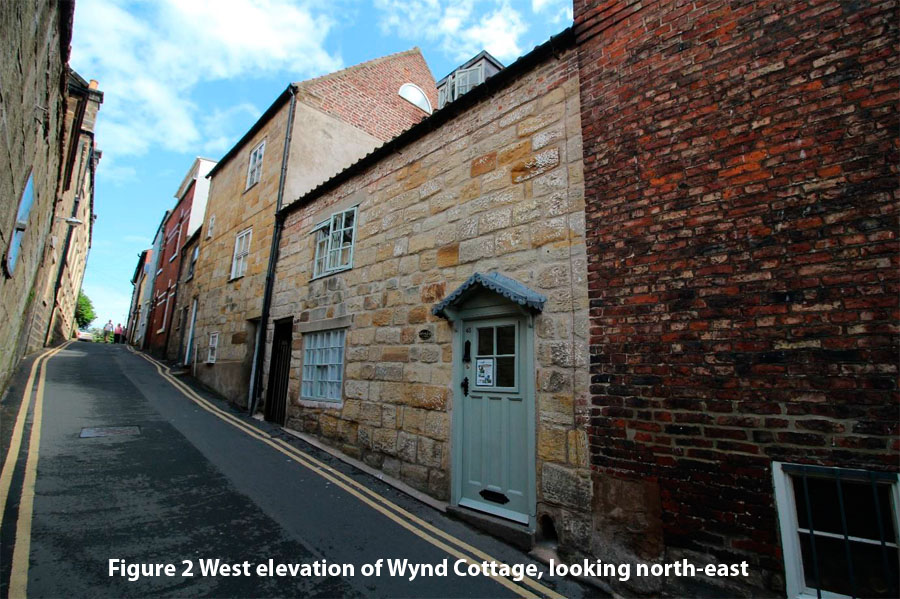

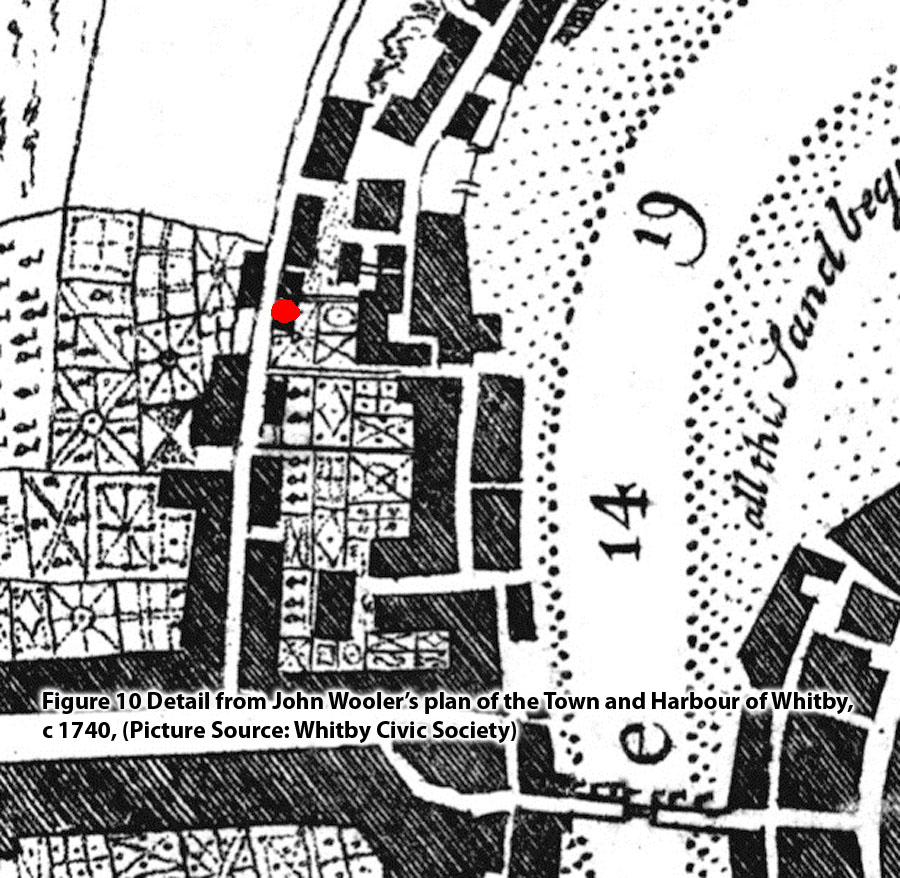

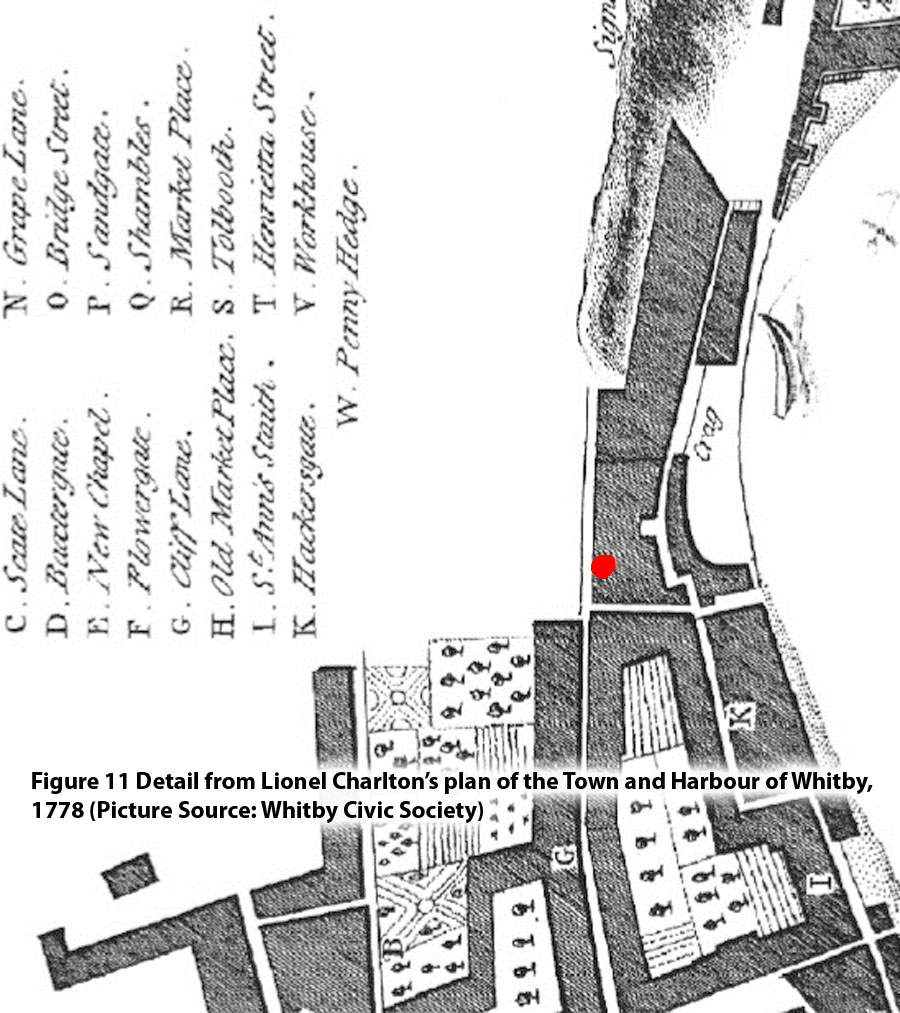

The principal frontage of Wynd Cottage is the west elevation which faces onto Cliff Street (Figure 2 and Figure 12). It is comprised of coursed and dressed ashlar sandstone bonded, in places, with earth mortar. This may have been sourced from the Saltwick formation of the North Yorkshire Moors which produced substantial amounts of Middle Jurassic stone used for historic building projects in Whitby (Powell 2012, 7). The masonry is bonded with that of 46-47 Cliff Street, the three-storey property to the north, and it seems likely that the two were constructed at the same time (Figure 12). The mapping evidence from c 1740 seems to confirm this as Wooler’s survey depicts a single structural block which is entirely detached to the north and south (Figure 10). There is a straight joint between the stonework of Wynd Cottage and the brick masonry of 44 Cliff Street, to the south (Figure 2). Historic mapping indicates that the latter was probably constructed between c 1740 and 1778 (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

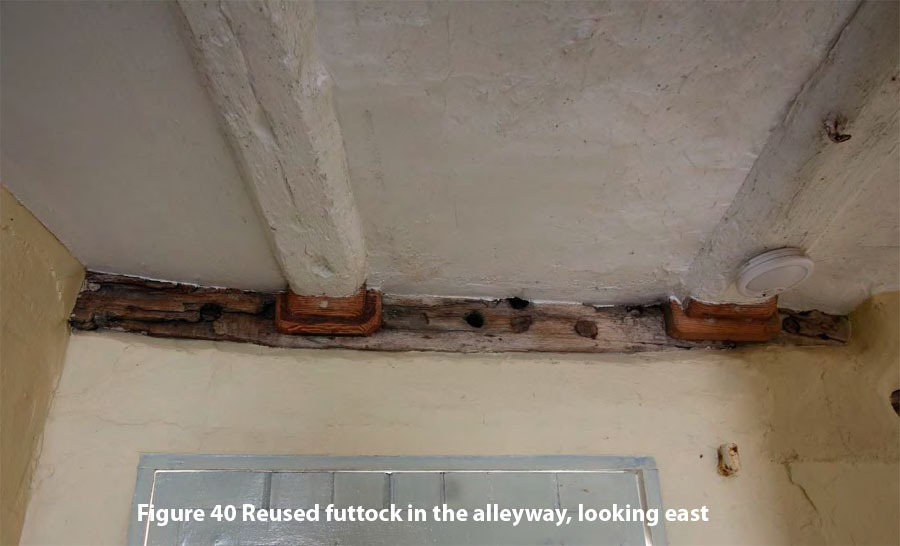

At ground storey there are doorways at the extreme north and south ends of the building. The doorway to the north has an iron gate and drops two steps down into an alleyway, with rendered brick walls, which wraps around the north and east sides of the house (Figure 18). The plastered ceiling of the alley is supported on two longitudinal chamfered beams. The northern beam is a modern insert, it has three hooks in its south face and is supported centrally by a timber post. The eastern end of the southern beam is housed within a reused futtock from a marine vessel (see below for further comments on reused ship or boat timbers).

At ground storey there are doorways at the extreme north and south ends of the building. The doorway to the north has an iron gate and drops two steps down into an alleyway, with rendered brick walls, which wraps around the north and east sides of the house (Figure 18). The plastered ceiling of the alley is supported on two longitudinal chamfered beams. The northern beam is a modern insert, it has three hooks in its south face and is supported centrally by a timber post. The eastern end of the southern beam is housed within a reused futtock from a marine vessel (see below for further comments on reused ship or boat timbers).

The alley was probably the original entry to the property. It is relatively common throughout the north of England for the day-to-day access to houses to be via a door at the back or side, even where there is a street front door. Here, on Cliff Street, there seem to be a number of other properties which were originally reached via side alleys, including Number 44, to the south, which still lacks a door fronting onto the street.

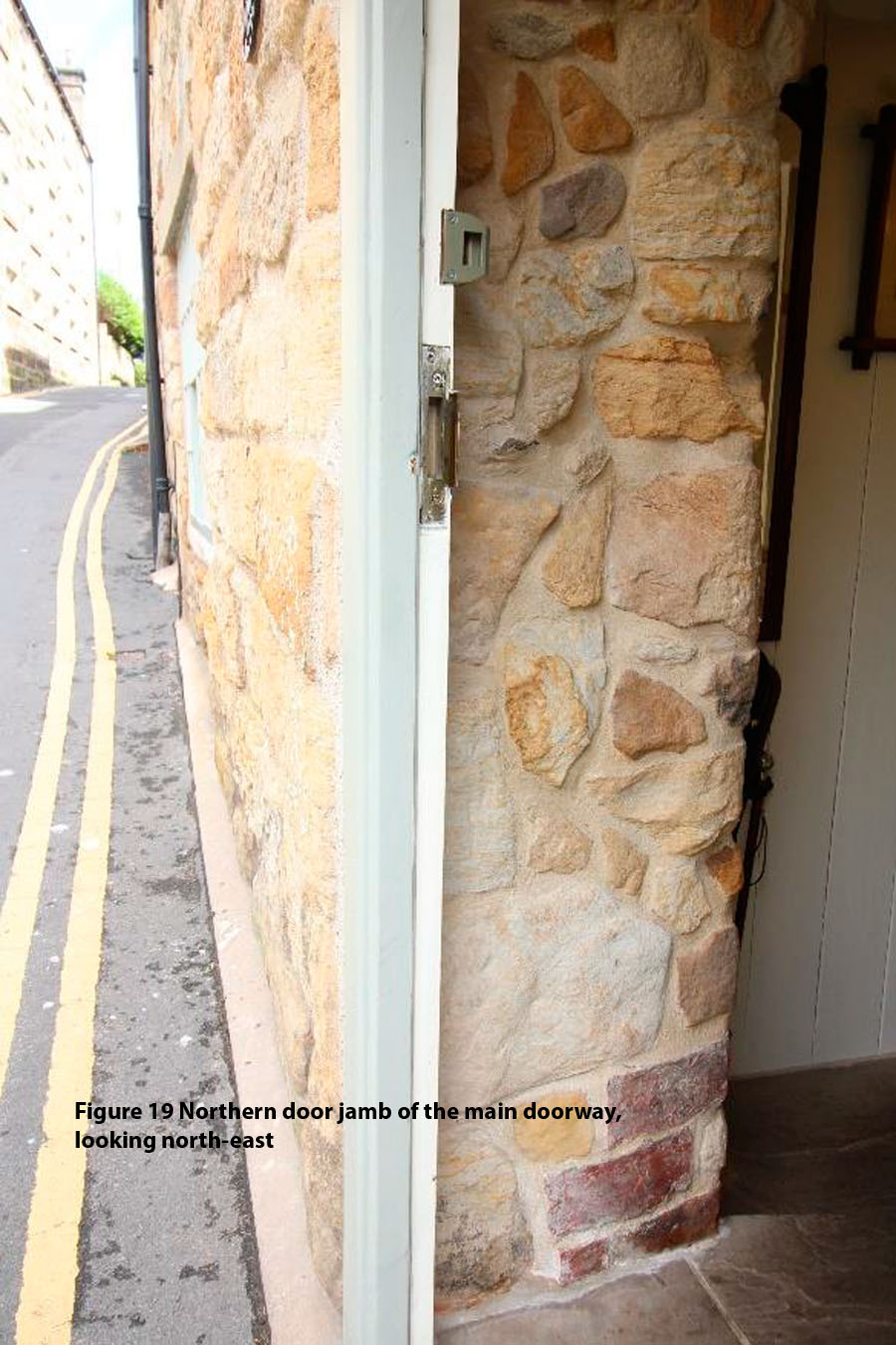

Immediately to the south of the alley gate is a modern timber-framed casement window, with a rendered lintel, which lights the kitchen within. The current front doorway lies at the south end of the elevation. The ragged nature of the masonry of the jambs suggest that it might possibly be a later insertion (Figure 19). It has a modern timber door with a four-pane window and a corbelled, lead-covered porch canopy over. To the south of the doorstep is the aperture for a boot scraper which has been removed.

Immediately to the south of the alley gate is a modern timber-framed casement window, with a rendered lintel, which lights the kitchen within. The current front doorway lies at the south end of the elevation. The ragged nature of the masonry of the jambs suggest that it might possibly be a later insertion (Figure 19). It has a modern timber door with a four-pane window and a corbelled, lead-covered porch canopy over. To the south of the doorstep is the aperture for a boot scraper which has been removed.

Above the ground floor window is modern timber-framed casement window with a rendered lintel, which lights the first-floor bedroom within. The masonry immediately above the rendered lintel features six courses of handmade bricks which lie directly on top of the stonework referred to above. This seems to be evidence that the original line of the eaves has been raised. The roof is clad with pantiles and has a single dormer gable with a modern timber-framed window which lights the second-floor landing. A handmade brick chimney stack rises through the ridgeline against the south elevation and has two ceramic chimney pots.

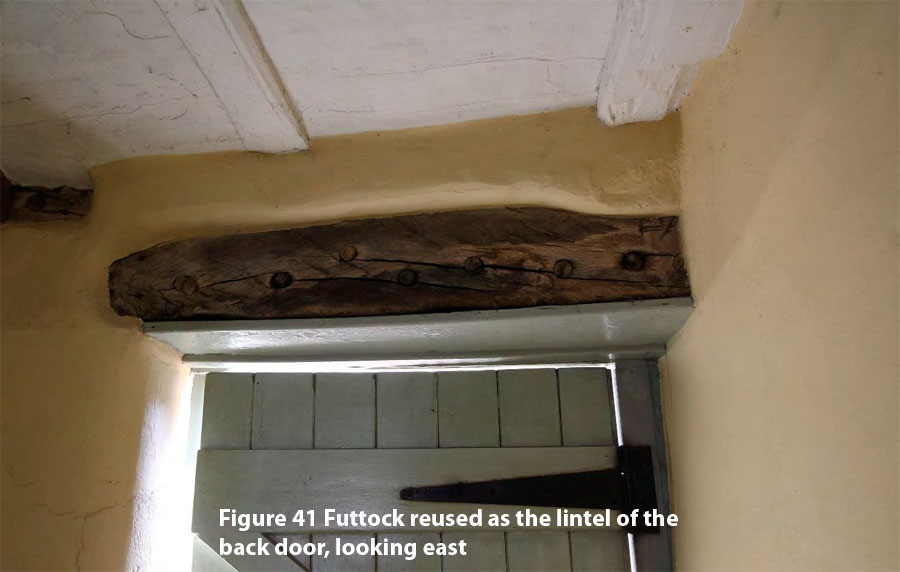

The rear, east, elevation is entirely rendered and painted (Figure 20). Conservation work by the landowners revealed that it is ashlar stone to first floor level and brick above. This elevation may have been partly rebuilt. The brick wash house, built during the second quarter of the twentieth century, masks the extreme north end of the ground floor elevation. The back door is situated off-centre and accesses a small lobby within the footprint of the southern return of the alleyway leading from Cliff Street. Above the modern planked door is a recessed segmental arch that may be a partial blocking of an earlier formation of the doorway. The internal lintel is reused from a marine vessel (see below). To the south of the door is a modern, timber-framed, four pane window which lights the dining room. Above, is a modern timber-framed casement window which lights the living room. To the north is a single pane, side-pivot window which lights the bathroom. The eastern pitch of the pantile roof is interrupted by two off-centre dormer gables with modern uPVC windows which light the second-floor bedrooms.

The rear, east, elevation is entirely rendered and painted (Figure 20). Conservation work by the landowners revealed that it is ashlar stone to first floor level and brick above. This elevation may have been partly rebuilt. The brick wash house, built during the second quarter of the twentieth century, masks the extreme north end of the ground floor elevation. The back door is situated off-centre and accesses a small lobby within the footprint of the southern return of the alleyway leading from Cliff Street. Above the modern planked door is a recessed segmental arch that may be a partial blocking of an earlier formation of the doorway. The internal lintel is reused from a marine vessel (see below). To the south of the door is a modern, timber-framed, four pane window which lights the dining room. Above, is a modern timber-framed casement window which lights the living room. To the north is a single pane, side-pivot window which lights the bathroom. The eastern pitch of the pantile roof is interrupted by two off-centre dormer gables with modern uPVC windows which light the second-floor bedrooms.

The north elevation is shared by 44 Cliff Street and the south elevation is mostly abutted by 43 Cliff Street. The south-east corner of Wynd Cottage does project further to the east of the later brick-built property to the south, but this was inaccessible at the time of the survey due to the separate ownership of the adjacent garden from which it could be viewed. This corner of the property has a high gable.

Interior of Wynd Cottage

Ground Floor

It is anticipated that the ground floor of the building was originally a single room that was used as a combined living space and kitchen, known regionally as a housebody. The dining room is floored with modern boards and has slates laid in the fireplace, which is located against the south elevation (Figure 21). The latter is of inglenook design and has a plain chamfered timber lintel, which has relict mortises that may be indicative of its reuse from elsewhere. The lintel supports two timber brackets of which the west example is reused from a marine vessel (see below). The original chimney may have been a timber-framed firehood rather than a masonry structure. Firehoods were common in northern houses during the seventeenth century but were generally replaced in masonry during the eighteenth century (Giles 1986, 139-40). This seems to have occurred and handmade bricks measuring 105mm (breadth) by 60mm (thickness) by 240mm (length) were employed in the construction. Within the hearth a new flue was created in brickwork. The fireplace has a modern wood burner set within the masonry.

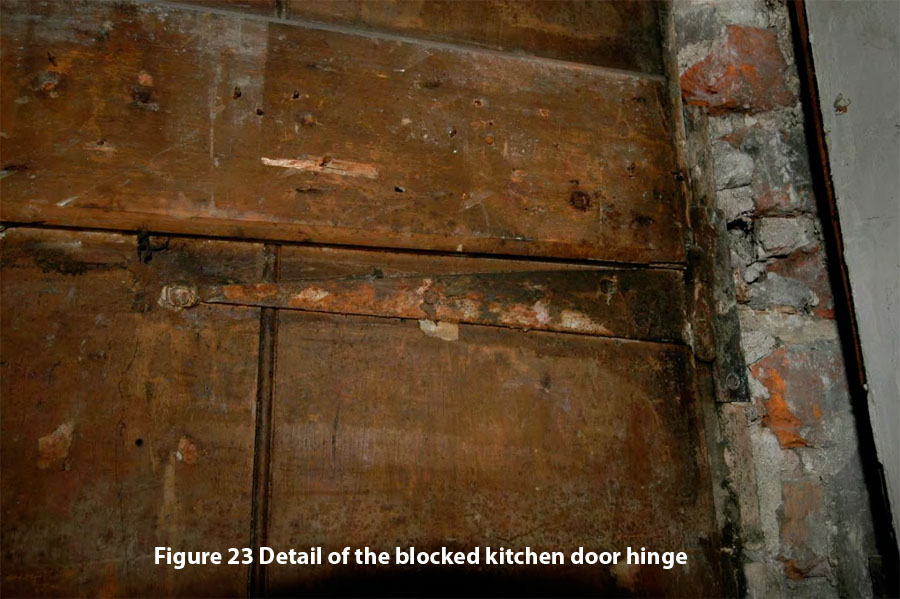

Opposite the fireplace is a blank elevation which contains the “ghost” of the former location of a fixed dresser within the plasterwork (Figure 22). Such features were common in domestic houses from the seventeenth through to twentieth centuries (Hall 2005, 199-201). The north-west corner of the housebody has been subdivided by close-board walls to create a separate kitchen (Figure 22). Formerly, there was a doorway leading from this room directly into the alleyway, which has now been blocked. The plank and batten door is still in-situ behind the modern appliances and has a machine-made T-shaped tapered hinge with a round end that probably dates to the nineteenth century (Figure 23; Hall 2005, 51-52).

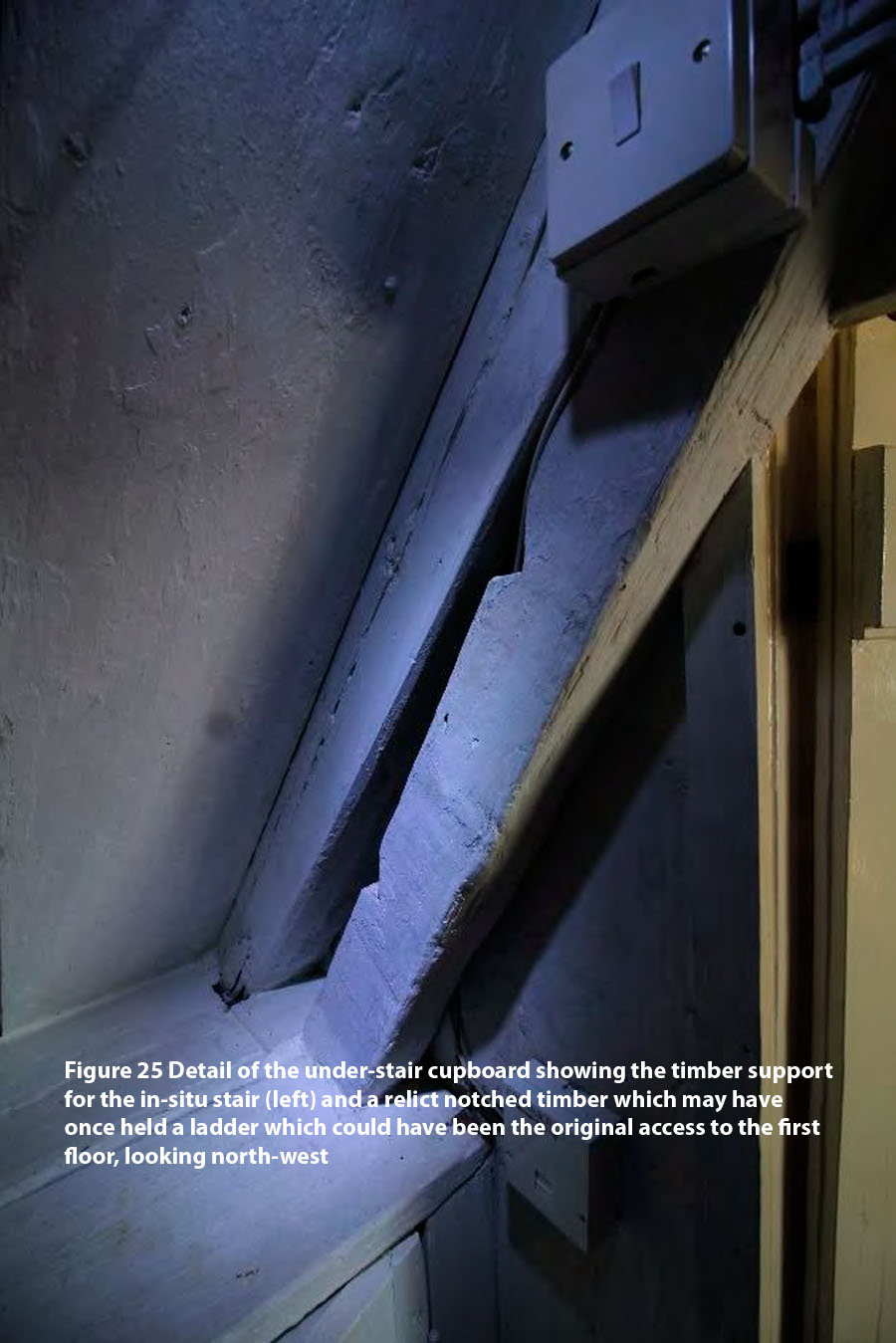

To the south of the kitchen is a stair hall which is accessed from both the dining room and the front door off Cliff Street (Figure 24). The stairs rise easterly in a straight flight from the south-west corner of the building. There is an under-stair cupboard to the west of the housebody fireplace. Within there is evidence that the current stair is a secondary addition and that part of the primary timber frame of a notched ladder survives (Figure 25). This was potentially the original way that the upper floor was reached. There is further evidence for a general remodelling of the first floor, which is supported by six chamfered joists that are orientated east to west, in the form of a relict joist ledge in the south elevation of the stair well (Figure 26). The ledge is one course of masonry higher than the present first floor and indicates that the joists were probably once orientated north to south. The reorganisation of the floor level and stair access may have taken place at the same time as the remodelling of the fireplace and chimney – possibly during the eighteenth century.

First Floor

In common with the ground floor, the first floor may once have been a single space, which probably functioned as an unheated bedchamber and store. It is now subdivided with close-boarded walls, similar like that of the kitchen downstairs, into a living room to the east (Figure 27 and Figure 33), a bedroom to the west (Figure 28), a bathroom within the north-east corner (Figure 29), and a stair lobby in the south-west corner. All the first-floor doors are softwood four panel softwood, characteristic of the late eighteenth or nineteenth centuries (Figure 30; Hall 2005, 42-43). The doors have evidence for “ghost” butterfly hinges (Figure 31). There are two blocked cupboard doors, set one above the other, in the close-board wall between the stair lobby and bedroom which contain in-situ butterfly hinges (Figure 32). Butterfly hinges were popular throughout the later sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Hall 2005, 52-53). Elements of the brick chimney breast have been variously plastered, painted, or panelled (Figure 33). The hearth is supported by hidden corbelling within the dining room below. The segmental arched fireplace has a modern wood burner within a modern surround. There is a fitted cupboard immediately to the east with softwood stable doors.

The bathroom has exposed floorboards which are approximately 265mm in width (10 ½ inches) and are laid on top of historic boards with similar dimensions that are consistent with an eighteenth-century date (Hall 2005, 165) and may be further evidence for the reorganisation of the floor level noted above. There is a blocked door to the west of the current access from the living room.

There are eight east to west orientated ceiling joists which are adorned with ovolo mouldings. The joists rest above the timber lintel of the window of the bedroom in the same stratigraphic context as the west elevation brickwork that appears to be evidence for the raising of the roof eaves (Figure 28).

Second Floor

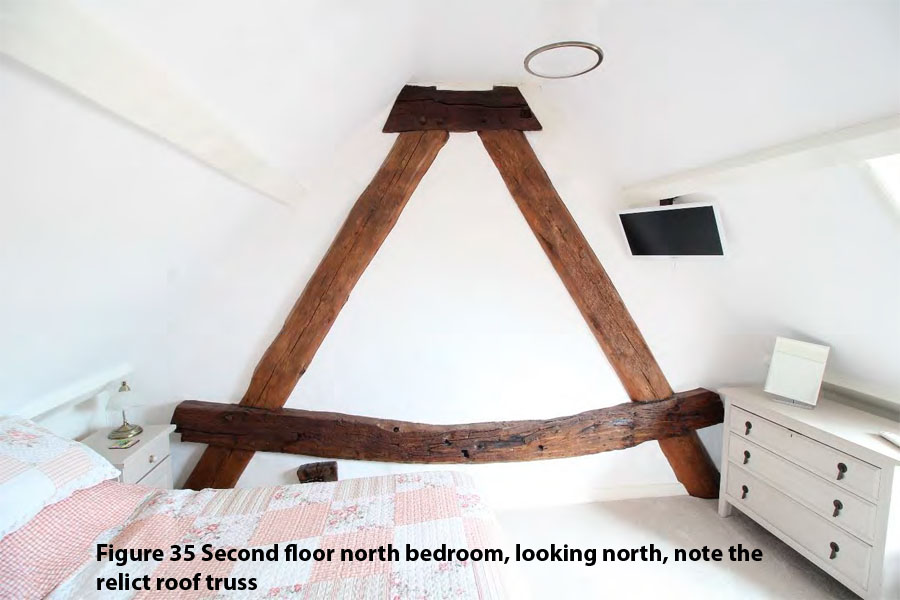

The winder staircase rises, from the first-floor stair lobby to the east against the south elevation. It grants access to a landing at second floor, which is lit by a dormer gable window in the west pitch of the roof structure (Figure 34). The second floor is an attic storey and contains a bedroom to the east of the landing with another bedroom to the north (Figure 34 and Figure 35). Both bedrooms are lit to the east by casement windows set within dormer gables.

The south elevation houses the projecting brick chimney stack, but this floor was probably unheated originally as there is no evidence for a hearth. Behind the chimney are angled rebates in the masonry of the cottage (Figure 34). This feature possibly represents a support ledge for a bracket associated with the earlier timber-framed firehood or rebates which may have supported the purlins of a relict roof structure (see below).

Roof Structure

There is evidence surviving for two roof structures at Wynd Cottage. The present in-situ structure is of softwood common rafter design. The east and west pitches are supported by two rows of purlins which are orientated north to south (Figure 34 above). The lower purlins are located just below the cill level of the west dormer gables and the upper purlins are positioned level with its head, probably indicating a contemporary creation. However, the purlins have been cut on the east pitch to insert the dormers. The roof structure and west dormer are probably part of a contemporary build, inserted to create the attic storey of the cottage to provide more accommodation during the eighteenth century. This may have occurred when the chimney, internal subdivisions and first-floor level were reorganised.

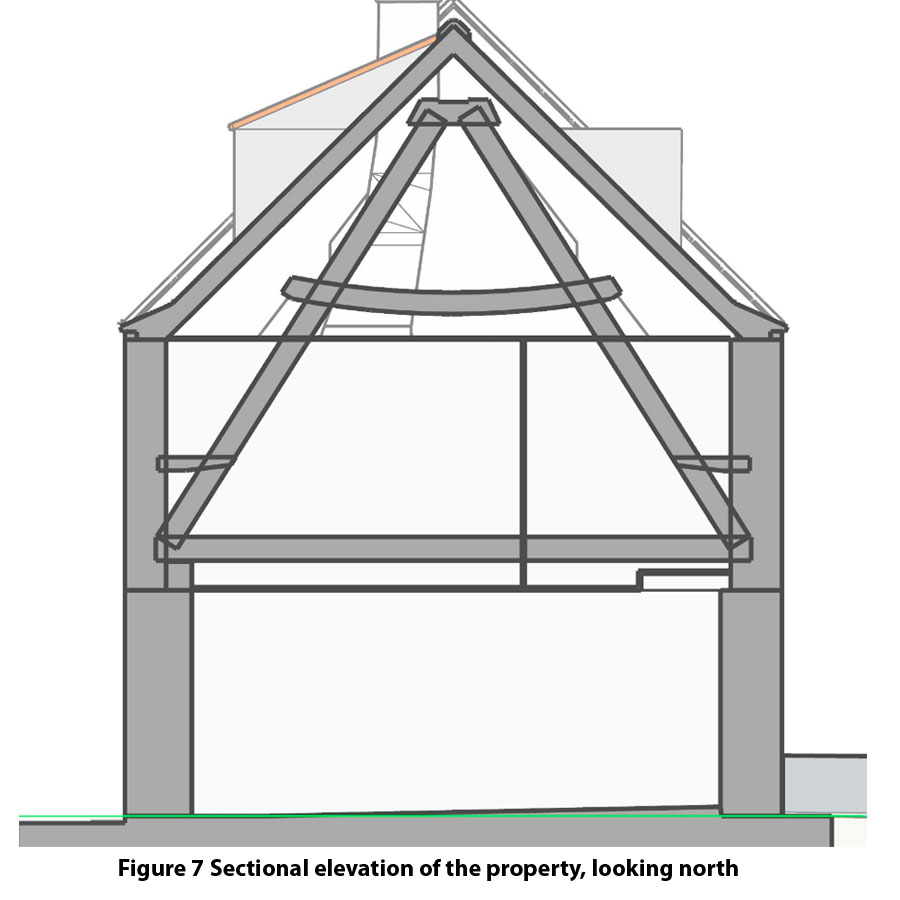

The north elevation of the first and second floor features an entire relict principal truss from an earlier roof structure (Figure 7). At first floor level a tie beam is visible for most of its length in the bedroom to the west (Figure 28 above) and in the bathroom to the east (Figure 29 above). Its soffit is located just above the floor and is approximately level with the relict joist ledge on the south elevation. This is taken as further evidence for the reorganisation of the first-floor level (see above). The tie beam is carried by the masonry of the building and supports the principal rafters. The rafters are retained into the masonry of the east and west elevations with slotted tapering dovetail spurs (Figure 36). The upper part of the structure can be seen in the north bedroom at second floor level (Figure 35 above). It has a curved collar which projects beyond the rafters, and the principal rafters are coupled at their apex with a saddle or yoke (Figure 37).

The north elevation of the first and second floor features an entire relict principal truss from an earlier roof structure (Figure 7). At first floor level a tie beam is visible for most of its length in the bedroom to the west (Figure 28 above) and in the bathroom to the east (Figure 29 above). Its soffit is located just above the floor and is approximately level with the relict joist ledge on the south elevation. This is taken as further evidence for the reorganisation of the first-floor level (see above). The tie beam is carried by the masonry of the building and supports the principal rafters. The rafters are retained into the masonry of the east and west elevations with slotted tapering dovetail spurs (Figure 36). The upper part of the structure can be seen in the north bedroom at second floor level (Figure 35 above). It has a curved collar which projects beyond the rafters, and the principal rafters are coupled at their apex with a saddle or yoke (Figure 37).

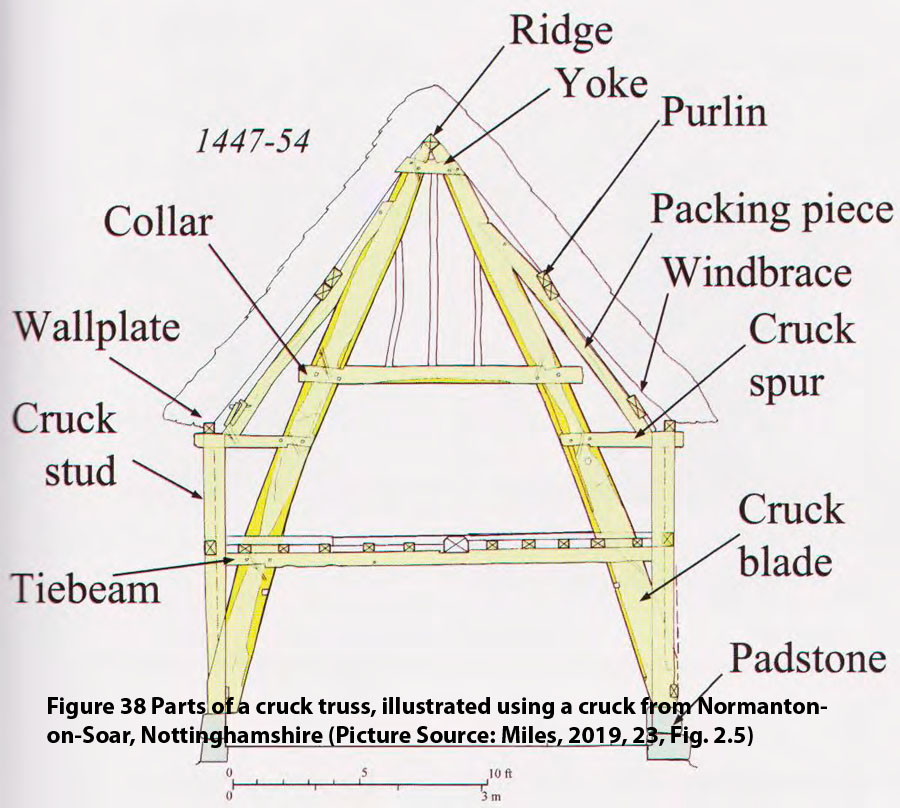

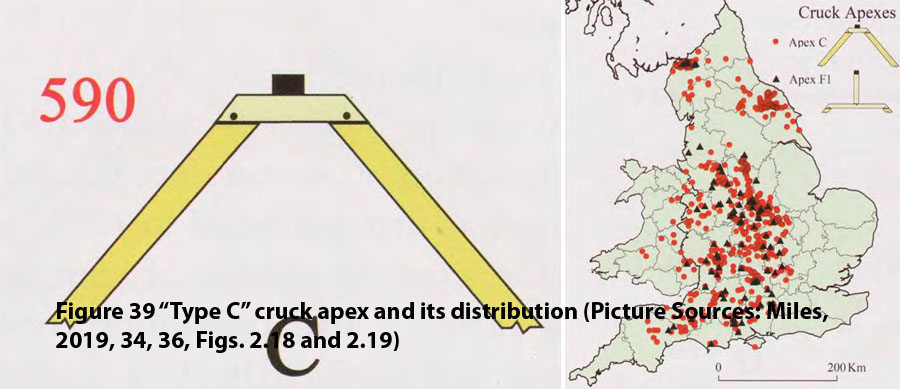

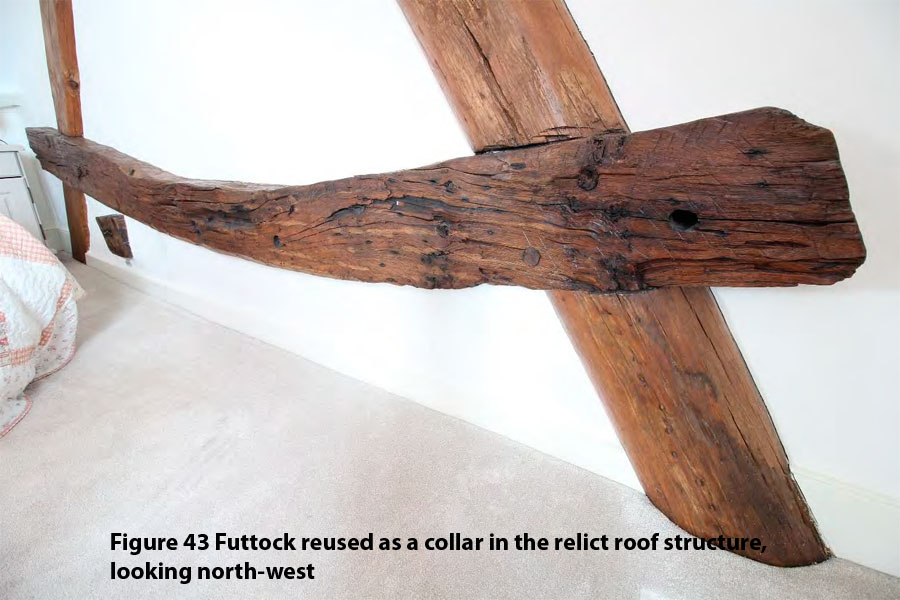

Elements of this assembly are reminiscent of cruck-frame construction (Figure 38). The spurs are familiar from this tradition, as are the rafters coupled with a yoke carrying a relict mortice for a ridge piece. Such a yoke is akin to the “Type C” apex known from cruck construction and was a popular traditional form across North Yorkshire (Figure 39; Miles 2019, 22-23, 34-36). Although this principal rafter roof is not a cruck-frame, it may have been constructed by carpenters either familiar with such traditions or even employing some timbers re-used from a cruck. One element of the structure which is certainly reused is the collar which has been reused from a marine vessel (see below).

The original appearance of the roof structure is a debateable point. It is possible that there may have been packing pieces which supported purlins and hence the common rafters (Figure 38). The packing pieces might be inferred as they would be required to carry the rafters down on to the summit of the corresponding masonry walls which rise much higher than the level of the tie beam. However, it is acknowledged that there was no visible evidence observed which could explain how such packing pieces may have been fixed to the principal rafters and such a formation would create a very shallow pitch. Alternatively, the masonry walls may have originally been lower. This would mean that the building was a single storey open to the rafters or a single storey with attic. If this was the case, then the protruding collar ends may have supported purlins to the north which were then carried by the rebates in the masonry of the south elevation. There also are some problems with this option, though, as there is no unambiguous evidence for a horizontal building break at the level of the tie beam and the presence of the spurs seems to point towards the contemporary existence of the masonry walls above the tie beams with the relict roof structure.

Timbers Reused from Marine Vessels

A total of four timbers that are suspected to be reused from marine vessels were identified at Wynd Cottage in the following locations:

- The lintel above the wash house door which has the longitudinal beam of the alley ceiling jointed into it (Figure 40).

- The lintel of the back door (Figure 41).

- The west bracket resting on top of the fireplace bressummer beam (Figure 42).

- The collar of the relict roof truss (Figure 43)

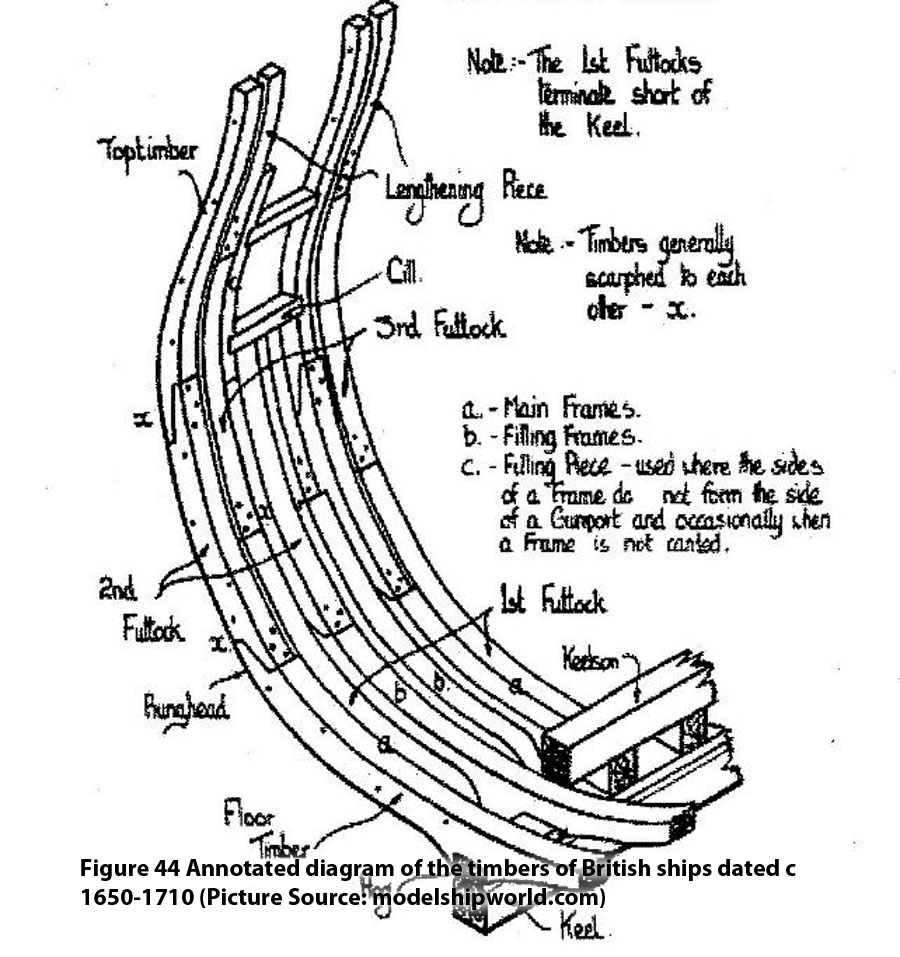

Archaeologically, the timbers were identified as marine in origin due to the curved forms of the alley lintel and truss collar in combination with the excessive number of large relict trunnels, measuring 30 to 40mm in diameter, found embedded within all four elements (see below). The timbers have been further authenticated by, the historic carpentry and shipbuilding specialist, Dr Damian Goodburn as being sections of futtocks from a carvel-built large boat or small ship (Damian Goodburn, pers. comm. email 10/05/2023). Futtocks are the curved oak timbers from the middle section of a vessel (Figure 44). The timbers have axe stop marks on which cut through an earlier patina, showing that the exposed face of the futtock was re-hewn a little to straighten them. The fastenings that pierce them are 'treenails' as archaeologists call them, or 'trunnels' or 'wrongnails' as boat builders have called them. The trunnels have facets from shaping and so were not 'mooted' as many nineteenth century examples were. The trunnel ends have expansion wedges still in place. In a sense, trunnels work like wooden rivets with both ends expanded, to lock them in place and make them watertight.

Unfortunately, futtock timbers like these are not closely dateable on woodworking details alone as the technology is well known from the early sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. However, the lack of obvious iron spike fastenings and bolts, which became common from the early nineteenth century, would suggest that a bracket in the earlier part of the date range is quite likely.

Unfortunately, futtock timbers like these are not closely dateable on woodworking details alone as the technology is well known from the early sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. However, the lack of obvious iron spike fastenings and bolts, which became common from the early nineteenth century, would suggest that a bracket in the earlier part of the date range is quite likely.

It must be stressed that it is unusual to find marine timbers reused in a terrestrial domestic setting. There is a common assumption that boats and ships were a near-constant source of timber for carpenters, and an incredibly large number of buildings are rumoured to include such elements. However, fieldwork and research by several specialists, including the author of this report, has demonstrated that it was not a widespread practice.¹

Despite this, there has been some very limited identification of marine timbers reused on land. Robin Lucas (1994, 1-3) has pointed to archival evidence for the practice in eighteenth century Norfolk. Dan Atkinson (2007, 11) has noted that the work of shipwrights differed from carpenters in the use of complex assembly marks, very large dimension timber and more numerous and sizable pegs in the joints. With the archival and archaeological context for the identification of marine timbers established, it has been possible for specialists to begin to tentatively point to potential examples, such as the possible ship’s mast reused as a tie beam at Waxham Great Barn, Norfolk (Moir 2003, 7).

It should be noted that, although finds are rare, reused marine timbers are more usually found in contexts immediately adjacent to the coast or navigable intertidal rivers. They are also found almost exclusively in post-mediaeval contexts, especially from the late eighteenth century onwards. This period was marked by a lack of available oak building timber, largely driven by the demands of the Industrial Revolution. Consequently, there was an uptick in the importation of softwoods from the Baltic regions and the employment of second-hand timbers by carpenters (Rackham 1986, 91-92; Brunskill 1985, 28).

As a post-mediaeval structure lying adjacent to Whitby Harbour (Figure 3 and Figure 4), which has a rich history of shipbuilding (Barker 2011; Jones 1982), Wynd Cottage is perhaps a prime candidate to have marine timbers present in its fabric. The timbers were found in both the primary build of the property as well as the eighteenth-century remodelling. It is somewhat remarkable that 45a Cliff Street, to the east, which was probably constructed around the same time as the remodelling of Wynd Cottage in the eighteenth century, also contains a similar marine timber. Here another futtock has been reused as a lintel over the original western doorway (Figure 45). It is likely that further survey of historic buildings in Whitby may yield more reused marine timbers.

¹ For example see: Mediaeval Mythbusting Blog #13: Ship Timbers https://triskeleheritage.triskelepublishing.com/mediaeval-mythbusting-blog-13-ship-timbers/ [Accessed 28/07/2023]. This online article hosted by Triskele Heritage will form the basis of a more detailed book chapter due to be published by The History Press in 2024.

2. Archaeological Description (this page)

James Wright has also publish this report on his website "Wynd Cottage, Cliff Street, Whitby".